A brief overview about Linux processes.

Process

A process is simply an instance of an executing program. It consists of an executing program, its current values, state information and the resources used by the operating system to manage the execution of that process.

In a UNIX-based system, each process is isolated from each other. From the viewpoint of the process, it appears to have control over and access to all the system resources as they were all of their own.

From the kernel’s point of view, a process consists of user-space memory containing program code and variables used by that code, and a range of kernel data structures that maintain information about the state of the process. The information recorded in the kernel data structures includes various identifier numbers (IDs) associated with the process, virtual memory tables, the table of open file descriptors, information relating to signal delivery and handling, process resource usages and limits, the current working directory, and a host of other information.

Process ID and Parent Process ID

Each process has a process ID (PID), a positive integer that uniquely identifies the process on the system. Process IDs are used and returned by a variety of system calls. For example, the kill() system call allows the caller to send a signal to a process with a specific process ID

The getpid() system call returns the Process ID of the calling process:

#include <unistd.h>

pid_t getpid(void); /* Always successfully returns the process ID of caller */

The init process always has process ID 1. The Linux kernel limits process ids to being less than or equal to 32,767. Once it reaches this number, the kernel resets its process ID counter so that it stars from a lower integer value. On Linux, its reset to 300 rather than 1 as many low-numbered process IDs are in permanent use.

The default process ID limit can be changed via the file /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max.

On 32 bit systems the limit is 32,768, but on 64-bit systems this number can be

anywhere uptil 2^22.

Each process has a parent that created it. The parent process id can be found out using getppid() system call:

#include <unistd.h>

pid_t getppid(void); /* Always successfully returns parent process ID of caller */

The parent of any process can also be found out by looking at the Ppid field provided

in the linux specific file /proc/PID/status.

Note:: If a child process becomes orphaned because its parent process terminated, the child is adopted by the init process, and subsequent calls to getppid() in the child returns 1.

Process Memory layout

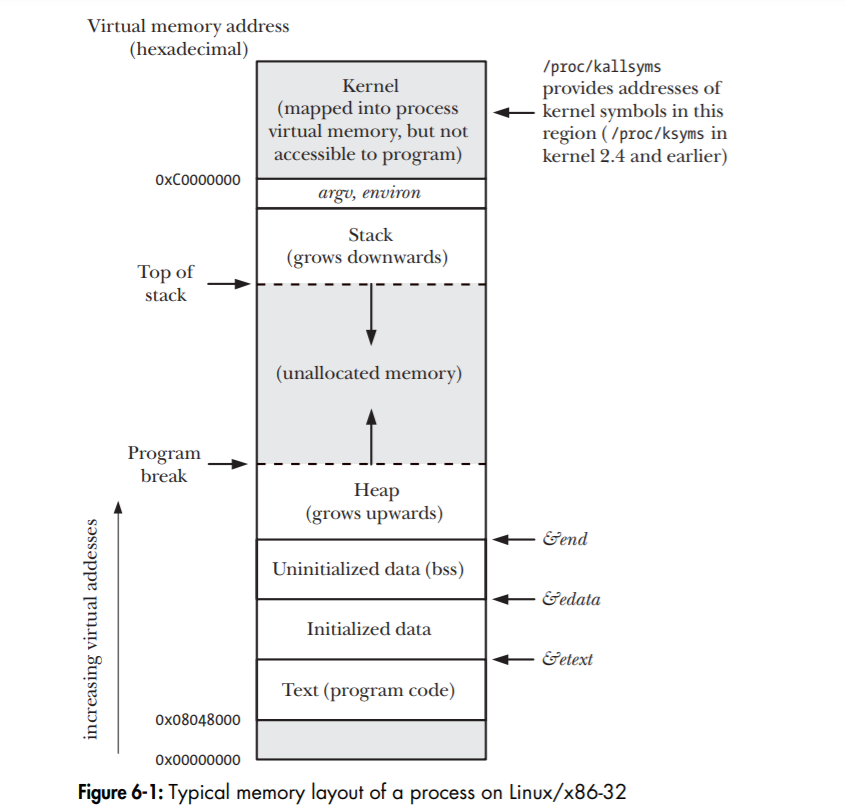

The memory allocated to each process is composed of a number of parts referred to as segments:

The text segment contains the machine language instructions of the process code. The text segment is made read only so that it cannot be accidentally modified by a bad pointer. Since many processes run the same program, it is also made shareble so that a single copy of the program code can be mapped into the virtual address space of the processes.

data segments:

The initialized data segment contains global and static variables that are explicitly initialized.

The uninitialized data segment contains global and static variables that are not explicitly initialized. Before starting the program, the system initializes all memory in this segment to 0. For historical reasons, it is also called the bss segment, a name derived from an old assembler mnemonic for “block started by symbol”.

The reason for this separation is that space for uninitialized data is not necessary to be allocated to the program on disk. The executable only needs to store the location and size required for the uninitialized data segment and this space is allocated by the program loader at runtime.

The stack is a dynamically growing segment. A function stores the function’s local variables, arguments and return addresses on the stack.

The heap is an area from which memory can be allocated dynamically during runtime.

Virtual Memory

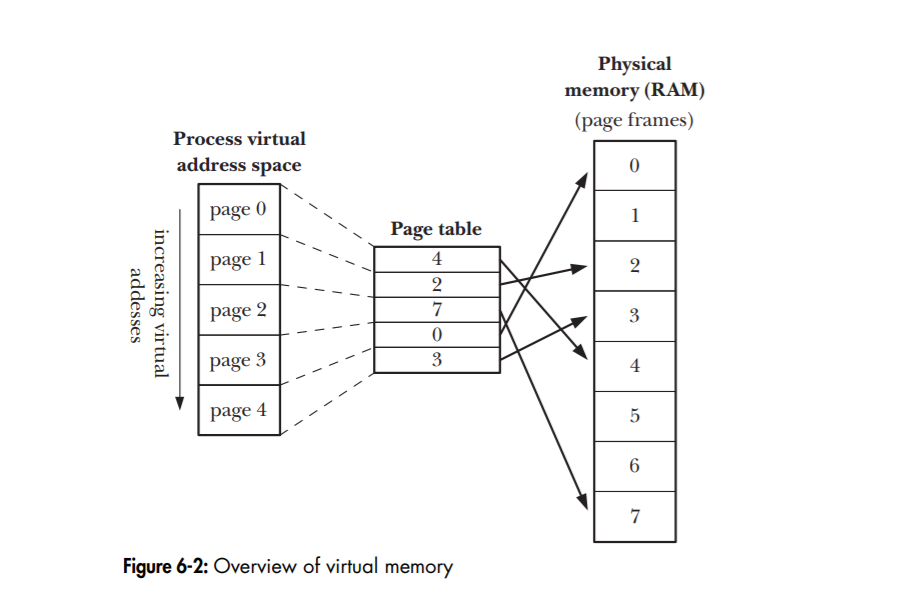

The memory layout we are talking about is the process’s virtual memory. A virtual memory scheme splits the memory used by each process into small units called pages. Correspondingly RAM is divided into a series of page frames of the same size.

In order to support this organization the kernel maintains a page table for each process. The page table describes the location of each page in the process’s virtual address space (the set of all virtual memory pages available to the process). Each entry in the page table either indicates the location of a virtual page in RAM or indicates that it currently resides on disk (swap).

At any one time, only some of the pages of a program need to be resident in physical memory page frames; these pages form the so-called resident set. Copies of the unused pages of a program are maintained in the swap area—a reserved area of disk space used to supplement the computer’s RAM—and loaded into physical memory only as required.

If a process refer to a page that is not currently on physical memory, then a page fault occurs, at which stage kernel suspends execution of the process till the page is loaded from disk into memory.